1942

Nisei journalist James Omura testifies at Tolan Committee hearings, opposing the evacuation saying, “Has the Gestapo come to America?”

Minoru Yasui, from Hood River, Oregon, the first Nikkei attorney in Oregon, was also the first to challenge the constitutionality of the military orders leading to the internment/incarceration of the West Coast Japanese American community, by deliberately disobeying the first curfew order directed at all persons of Japanese ancestry. The district court found the curfew order unconstitutional as applied to citizens, but nonetheless convicted Yasui, finding that he had relinquished his citizenship by working as a bilingual assistant for the Chicago Japanese Consulate. On June 21, 1943, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld Yasui’s conviction on the curfew violation, relying on its same-day decision in Gordon Hirabayashi’s case, which found the curfew orders constitutional as applied to all persons of Japanese ancestry. In January 1983, based on discoveries by Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga and Peter Irons that critical evidence showing that Japanese Americans posed no threat to national security had been intentionally destroyed, altered and suppressed in the wartime cases, a team of mostly Sansei lawyers mounted a coram nobis challenge to the constitutionality of Yasui’s wartime conviction, which resulted in his conviction being vacated in January 1984.

Fred Korematsu of Oakland, CA, seeking to avoid the military orders and leave the West Coast with his Italian-American girlfriend, disobeys the exclusion/confinement order forcibly removing the Bay Area Japanese American community to Tanforan Assembly Center and is arrested on May 20, 1942. On Dec. 18, 1944, the Supreme Court upheld Korematsu’s conviction and the constitutionality of the military exclusion order, notwithstanding strong dissents from three Justices. In January 1983, based on discoveries by Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga and Peter Irons that critical evidence showing that Japanese Americans posed no threat to national security had been intentionally destroyed, altered and suppressed in the wartime cases, a team of mostly Sansei lawyers mounted a coram nobis challenge to the constitutionality of Korematsu’s wartime conviction, which resulted in his conviction being overturned in November 1983, by Judge Patel of the San Francisco federal district court. While the successful coram nobis actions undermined the factual basis of the Supreme Court’s wartime decisions, the decisions themselves still stood until June 26, 2018, when Supreme Court Chief Justice Roberts, writing for a 5-4 majority upholding the constitutionality of Pres. Trump’s Muslim Ban executive order, declared in dicta that the Korematsu decision “has no place in law under the Constitution.”

Gordon Hirabayashi, a University of Washington student in Seattle, WA, deliberately disobeys both the curfew and exclusion/confinement orders, presenting to the local FBI office a statement titled, “Why I Refuse to Register for Evacuation.” On June 21, 1943, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the curfew orders, and Hirabayashi’s conviction, as applied to all persons of Japanese ancestry. However, the Supreme Court was able to avoid ruling on the constitutionality of Hirabayashi’s conviction on the exclusion/confinement orders. Hirabayashi later refuses to fill out the loyalty questionnaire and as a conscientious objector, refuses to be drafted into the Army. In January 1983, based on discoveries by Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga and Peter Irons that critical evidence showing that Japanese Americans posed no threat to national security had been intentionally destroyed, altered and suppressed in the wartime cases, a team of mostly Sansei lawyers mounted a coram nobis challenge to the constitutionality of Hirabayashi’s wartime convictions, which went to trial before Judge Voohees of the Seattle federal district court in 1986 and ultimately resulted in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals overturning both of his wartime convictions in September 1987.

Sit-down strike of 100 prisoners, many of whom were women assigned to work on camouflage nets for the Army, who had to meet high net quotas, were forced to labor under the hot sun, often in a kneeling position for eight-hours with inadequate food and water. Many of the workers were also allergic to the hemp nets, burlap, and dyes used in the operation. The strike was successful in getting some changes made.

Mitsuye Endo, incarcerated at Tule Lake and Topaz War Relocation Authority centers, filed a federal habeas corpus action in San Francisco federal district court challenging the government’s constitutional authority to hold her in custody as a loyal American citizen not charged with any crime. On December 18, 1944, the same day the Korematsu decision issued, the Supreme Court unanimously decided that the WRA lacked delegated authority to hold “citizens who are concededly loyal" in the WRA camps, but did not reach the constitutional issues presented. The decision validated the decision the government had already made to close the camps and allow Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast.

“Riot” due to poor living conditions and repressive searches; 200 military police called in; martial law declared with tanks and machine guns; 11 young men under age 20 were separated from their families and sent to Tule Lake.

On September 6, 1942, the strain of working under white supervisors and the frustration of late food deliveries and thefts drove an inmate cook to physically attack a Caucasian worker with a kitchen knife. The latent antagonism between white authorities and inmates came to boil again one month later when military police arrested 32 young children for sledding outside of camp boundaries. Although the children were released to their parents, inmates were quick to condemn the treatment of the children by the police.

Amidst rising tension the Army attempted to recruit volunteer workers to construct a barbed wire fence around the perimeter of the camp. The majority of working-age men went on strike, refusing to participate in the project. Three thousand inmates signed a petition "charging that the fence proved that Heart Mountain was indeed a 'concentration camp' and that the evacuees were 'prisoners of war.'"

Hundreds or possibly thousands of prisoners gathered in protest of the arrest of two Kibei, following the beating of Mr. Kay Nishimura, who many viewed as a corrupt government informant. One of the two arrested, George Fujii, had generally worked constructively with both his fellow internees and the administration – “a popular and civic-minded young man who had been active in community affairs.”

The Issei committee called for a strike which lasted about 10 days and shut down the entire Camp. Following the strike, inmates, notably Issei, played a larger role in determining the conditions under which they lived.

Brawl at Army training camp: Newly arrived white Texan soldiers from the 2nd Division taunted, pushed, shoved and swung heavy-buckled cowboy belts at the Nisei soldiers from the 100th Battalion. But many of these Nisei soldiers from Hawai’i were black belts in judo and sent 38 of the Texans to the hospital; only one Nisei was hospitalized from the fight. The white Texan soldiers at Camp McCoy never bothered the Nisei soldiers after that.

Tensions ran high at the Gila River Relocation Center when on Nov 30, 1942, Takeo Tada, a member of the Temporary Community Council, was badly beaten. One assailant was arrested sent to a local jail. The community regarded him as a hero for Tada was considered a traitor. These events resulted in power struggles that pitted Issei and Kibei against Nisei. The Issei generally were left out of the power structure at Gila but gradually regained power by forcing out Nisei/JACL oriented appointees by intimidation. Symbolic of their domination was a banquet for150 persons including WRA officials given by a powerful Issei on Jan 5, 1943, where the released assailant was toasted with forbidden bourbon and the administration was made to understand who were now running things.

The WRA reasserted power by arresting 15 Issei and 13 citizens, mostly Kibei on Feb. 16-17 as troublemakers, but the community had regained cultural identity and some self-determination and empowerment.

Multiple work stoppages protesting dangerous working conditions by prisoners who were being forced to fell trees for the camp’s fuel (37 woodcutters were injured and 1 killed in a trailer accident), and the large pay gap between what Nikkei and white staff were paid.

“Manzanar Riot” – JACL leader Fred Tayama had just come back from a JACL conference which advocated the draft. He was beaten by assailants on Dec. 5, 1942. Harry Ueno, a popular leader of the Mess Hall Workers Union was arrested for the beating of Tayama. 2,000-4,000 protesters gathered to demand Harry Ueno’s release. Discontent had also been building up at Manzanar with suspicions that white administrators were stealing food to sell on the black market and many other grievances. Soldiers fired into the crowd, and eleven prisoners were shot in the back; two died due to the lack of medical supplies in the clinic, one a teenage bystander. Martial law was declared. Many people wore black armbands in the following days as a badge of protest, and held an informal strike. Some protestors were sent to Citizen Isolation Centers (Moab, Leupp) and Tule Lake.

1943

U.S. government issues “Loyalty Questionnaire” to all prisoners and even to Nisei soldiers, to supposedly weed out the “loyal” from the “disloyal.” Question number 27 asked if Nisei men were willing to serve on combat duty wherever ordered Question number 28 asked if individuals would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. Both questions caused confusion, anger and divisions. Citizens resented being asked to renounce loyalty to the Emperor of Japan when they had considered themselves Americans and had never held loyalty to that Emperor in the first place. For Issei to answer yes to Question 28 would mean they would become stateless because they were barred from becoming U.S. citizens on the basis of racial exclusion. Most people were worried that how they answered these questions might cause their families to become separated. There were many reasons for why people answered, didn’t answer or modified their answers and these reasons had very little to do with loyalty or disloyalty.

Ultimately, by the end of the Loyalty Questionnaire process, approximately 16% of all individuals either refused to answer the questions, or gave qualified answers, or answered “no” to one or both of the "loyalty" question #’s 27 and 28. The frustration and anxiety caused by the Loyalty Questionnaire added to the anger about the United States government’s entire program of mass removal and incarceration, and laid more foundation for expressions of protest against the draft which was imposed the following year.

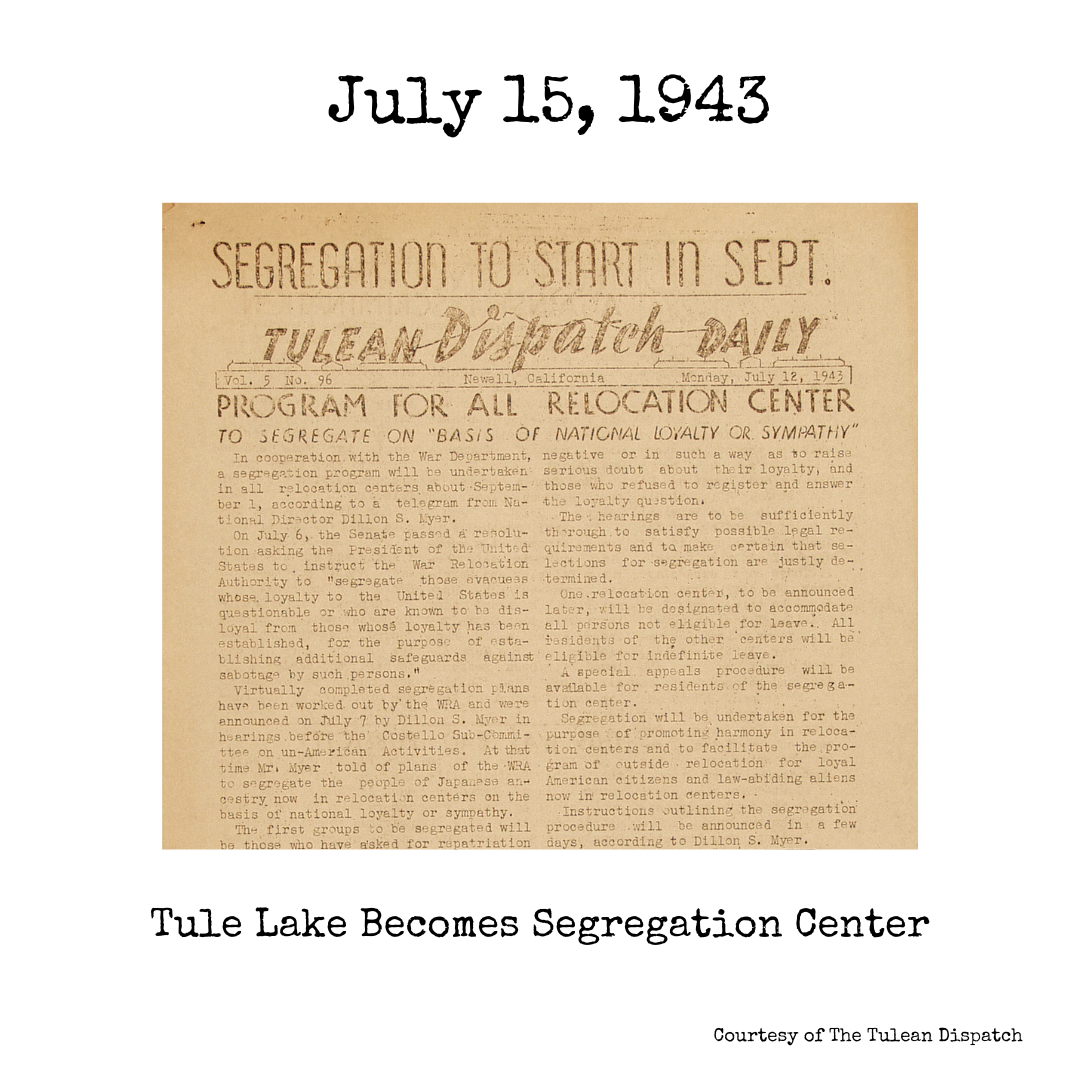

Over 12,000 of these prisoners were sent to Tule Lake which was now designated as a segregation center, including even people who answered “yes-yes” but who the WRA considered troublemakers regardless. Some of the so-called “disloyals” were not transferred to Tule Lake because Tule Lake had become far too overcrowded; some stayed where they were and some were transferred to Dept. of Justice camps or Citizen Isolation Centers.

Issei carried out a calm but firm and well-organized effort which resulted in an unusual victory, successfully making the government change the wording of Question #28 of the Loyalty Questionnaire from making them stateless to instead only asking if they would abide by the laws of the U.S. and not take action against the U.S. war effort. Under the leadership of the Issei, Topaz was the only camp where the entire population of the camp initially refused to register/sign the loyalty questionnaire and delayed registration until February 17, 1943.

Around 35 Tule Lake prisoners from Block 42 who had refused to register/sign the loyalty questionnaire were arrested. Most were sent to another camp 10 miles away, some were sent to the Moab Citizens Isolation Center in Utah.

The Heart Mountain Congress of American Citizens, is formed by Frank Inouye, as well as Kiyoshi Okamoto and Paul Nakadate (who were both also instrumental in the formation of the later Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee). The Heart Mountain Congress of American Citizens set forth 14 resolutions which articulated the many concerns that had been building up about Nisei civil/citizenship rights, the loyalty questionnaire and elimination of race-based discrimination in the military as a prerequisite to enlistment.

When Nisei were allowed to volunteer for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in April 1943, only 2.1% of eligible Nisei did so. Jerome tied with Rohwer for the lowest rate of volunteers at any camp. Earlier, inmates at Jerome subsequently answered question 28 in a manner other than "yes" at a higher rate than any other camp. With the advent of segregation, some 2,147 from Jerome were sent to Tule Lake "Segregation Center," about one-fourth of the population of Jerome.

April 25, 1943, some 120 Nisei soldiers at Ft. Riley, Kansas followed orders to fall out, expecting to line the roadside along with the rest of the soldiers when President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited for Easter services. Instead, the Nisei were marched in the opposite direction and led into an aircraft hangar while other soldiers pointed machine guns at them. Once the doors locked, all Nisei were ordered to sit on risers and remain silent. They were guarded, even escorted to the latrine in groups of ten by officers with drawn pistols. After Nisei soldier Hakubun Nozawa wrote to the War Department on behalf of the soldiers to protest this humiliating treatment, army officials intercepted his letter and demoted him.

Amid mounting conflicts between the white administrators and the Japanese American employees, 102 hospital employees participated in a walk-out, resulting in a five day strike.

At the insistence of Congress, the Army and the JACL, the camp at Tule Lake is designated as the Segregation Center. It becomes the most brutally punitive and repressive of all the camps. Some 12,000 Japanese Americans who had not answered “yes-yes” for a variety of reasons often having little to do with loyalty were forcibly relocated to Tule Lake from the other camps. Prior to this date, Tule Lake was not much different from other camps. But once it became the main place to segregate the so-called “disloyals” or “troublemakers,” more barbed wire was added and an eight-foot high double "man-proof" fence was constructed. The six guard towers surrounding the site were increased to twenty-eight, and a battalion of 1,000 military police with armored cars and tanks were brought in to maintain security. A stockade was built, where prisoners were tortured, beaten and starved. Tule Lake was overcrowded, had food shortages and very bad living conditions when martial law was imposed.

Strike by camp laundry and latrine maintenance workers, in protest of WRA’s reduction of paid jobs; women gather at office of the Acting Director to demand that he insure that the camp would have hot water.

Gordon Hirabayashi, the first Nikkei draft resister in WWII, arrives at Tucson Federal Prison (after convicting him, the government would not provide him transportation, so he had to hitchhike from Seattle to Tucson) to serve his term for refusing to fill out the loyalty questionnaire and as a conscientious objector, for refusing the draft. There were around seven other Japanese American conscientious objectors during WWII. Other Nisei imprisoned at the Tucson Federal Prison, including draft resisters from other camps called themselves “The Tucsonians.”

Coal strike at Tule Lake with workers demanding clothing allowance to pay for gloves and clothing to wear while shoveling coal. (The coal dust destroyed worker's shoes, pants, and shirts, and covered the worker’s faces and hands with black dust that didn’t wash off easily.)

Work stoppage by farm laborers to protest unsafe working conditions after one had been killed in a truck accident and several injured. There were numerous other labor protests at Tule Lake.

5,000 – 10,000 prisoners gather to present a list of 18 demands to WRA Director Dillon S. Meyer on his visit to Tule Lake. A group-appointed "Committee of 17" met with Myer, but all of their demands including removal of center director Ray Best were rejected. Future evacuee meetings in the administration area were then forbidden.

In response to Army proposals to cut work crews and to employ only “cleared” workers, coal, garbage and warehouse crews go on strike, which is ended when the Army declared martial law on Nov. 13.

A group of prisoners attempted to stop a truck driven by Caucasians, suspected of carrying stolen food meant for the prisoners out of camp to be sold on the black market. Several prisoners were arrested and brutally beaten by guards that night; martial law was declared with tanks and machine guns mounted on jeeps; hundreds arrested and put in the stockade. The period of martial law was a time of suffering and repression, with a curfew and an end to many activities. Only those in crucial service areas went to work; others remained idle with no income for months. There were shortages of milk, food, hot water and fuel to heat the barracks.

On December 11, a group of men in Poston’s Unit II pressured JACL President Saboru Kido into signing a letter declaring that the JACL delegates had been speaking only for themselves at their recent convention in Salt Lake City, not for the residents of Poston, and that the JACL’s resolution in favor of military service “d[id] not apply to [the] people of Poston, Arizona.” The next day they pressed further, forcing him to sign a statement that directly contradicted JACL policy:

“We will be willing to join the resolution of the JACL [seeking the draft] providing the U.S. government will recognize all of our constitutional and civil rights as American citizens by granting privileges to citizens and alien parents to return to their original places prior to evacuation, and that the U.S. government will reimburse us on losses incurred because of evacuation.”

A few weeks later, this second statement formed the basis of a strongly-worded petition to the President of the United States demanding restoration of civil rights that sixty-three Poston internees signed and sent off to Washington, DC. Even this public statement did not stem the anger that some at Poston were feeling about military service. Many showed up at the Army’s recruitment teams’ question-and-answer sessions to ask difficult and even hostile questions that emphasized the mistreatment and discrimination they were enduring.

Prisoners in the Tule Lake stockade begin the first of three hunger strikes to demand they be released to re-join their families in the camp.

1944

World War I lessons: Issei parents cautioned the draft-age Nisei to be wary of the government’s vague suggestion that their citizenship rights would be restored by enlisting for combat duty. “Issei parents knew from experience that the United States had fought to make the world safe for democracy in the past but had not in practice kept all its promises. Issei soldiers who volunteered to fight during WW I with the promise of citizenship had to fight for more than fifteen years to get their reward. Some Issei veterans did, in the end, get U.S. citizenship in 1935, but without mounting a sustained struggle, they knew that the government would not have voluntarily given this status to [these] veterans… “

Hiedo Murata, an Issei proud to have served in WWI, had committed suicide in Pismo Beach, CA in 1942 in response to the evacuation order. In his pocket he had put his certificate from Monterey County commending him for his WWI military service.

Selective Service draft: By the latter half of 1943, only 6% of the 19,963 Nisei of military age had volunteered from the camps to join the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team. This indicated the depth of discontent with how they and their families had been treated by the U.S. Government, as compared to the large enlistment numbers from Hawaii where Nisei had not been incarcerated. So on January 20, 1944, the U.S. government/Selective Service imposed the draft, to force the mainland Nisei to replenish the extremely high casualties of the 442nd combat team.

The government was demanding that the Nisei perform this duty as a citizen’s obligation, yet had taken away all of their citizen rights with no clear guarantees of when or even if those rights would ever be restored. While ultimately most eligible Nisei felt they had little choice and were drafted, an estimated 315 chose to express their patriotism by refusing the draft and were sent to federal penitentiaries and federal prison camps.

Fair Play Committee is activated and led the most organized effort to support draft resistance. These draft resisters were not “No-No” boys – they had answered “Yes-Yes” on the loyalty questionnaire and made it clear that they were absolutely willing to join the U.S. armed forces once their civil rights were restored. Meetings were held in mess halls throughout the camp, three or four times a week. These mess halls held close to 300 or 400 people and had standing room only crowds every night. Many were concerned about the injustice of being drafted out of these camps, even if they did not resist. The WRA outlawed these meetings once they realized what was being discussed, but the FPC continued holding these meetings anyway. On Feb. 23, 1944 James Omura publishes an editorial in support of the Heart Mountain draft resisters in the Denver, Colorado newspaper, the Rocky Shimpo.

On March 4, 1944, the Fair Play Committee issued a statement their draft age members would "refuse to go to the physical examination or to the induction if or when we are called in order to contest the issue" unless and until their constitutional rights were restored.

George Fujii/Voices of Nisei issues a statement calling for General DeWitt to apologize for his statement “A Jap is a Jap” and be expelled; for Such signs as “No Jap,” “You Rat,” “No Orientals or Colored admitted” be taken down across the U.S.; for Nikkei soldiers to have every opportunity to advance in Air Corps, in the Army, and in the Marine Corps, in integrated units, etc. He is later arrested and charged with sedition for these statements.

Mothers Society of Minidoka – statement signed by over 100 Issei mothers in support of their Nisei sons, calling upon the government to reconsider the Selective Service draft and to restore civil rights. Sent to President Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dept. of War, Director of WRA Dillon S. Meyer. The Mothers Society felt that an earlier draft written by Min Yasui was too weak, and decided to write the statement themselves.

11-point petition issued by the by the Amache Community Council in behalf of the center’s Nisei residents, sent to Director of the WRA Dillon S. Meyer, President Roosevelt and other government agencies. Among the requests: That all evacuees be accorded all the rights and privileges which the constitution of the United States gives them. That the right to become naturalized citizens of the United States be extended to the alien Japanese. That the United States Government establish adequate precautionary measures so that the sad experiences of evacuation will never again be repeated with the Japanese or with any other group because of race, color or creed.

Joint Resolution by Amache Blue Star Mothers and the Amache Womens Federation, as Issei mothers in support of their Nisei sons, calling upon the government to reconsider the Selective Service draft and to restore civil rights.

Mothers of Topaz – Petition signed by 1,141 Issei women in support of their Nisei sons, calling upon the government to reconsider the Selective Service draft and to restore civil rights. This Petition was sent to President Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, the Dept. of War, Director of the WRA Dillon S. Meyer, and Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior.

119 Issei and Nisei members of the Poston Women’s Club signed a resolution calling upon the government to delay the draft induction, arguing that with the WRA’s announcement that the camps were going to be shut down, that their Nisei sons and brothers were needed to help their families’ transition out of the camps.

More than one hundred Nisei/Kibei soldiers at Ft. McClellan sought appointments with their superior officers to raise concerns about how they had been treated by the military as well as discrimination endured by their families. When ordered to fall in, several Nisei soldiers broke ranks (reportedly to protest being called "yellow-bellied Japs," which the sergeant denied) 43 Japanese American soldiers are arrested. 50 others refused to collect their military gear, and eventually a total of 106 are arrested for their refusal to participate in combat training. 21 are convicted and sent to prison. These men became known as the “Disciplinary Barrack Boys/DB Boys.” It was not until 1983 that their dishonorable discharges were corrected to honorable, but still their court-martial convictions were not set aside. Other Nisei soldiers from Camp Grant, Illinois, Ft. Wood, Missouri and Ft. Meade, Maryland also refused combat training and were sentenced to hard labor and imprisonment, some not being released until 1950.

U.S. Marshals arrive to arrest the first 12 of an eventual total of 85 Nisei from Heart Mountain who refused to be drafted. The Heart Mountain draft resisters were tried and convicted of Selective Service Act violations in the largest mass trial for draft resistance in U.S. history. They were sentenced to two to five years and sent to McNeil Island (Washington) and Leavenworth (Kansas) federal penitentiaries.

Martial law at Tule Lake was imposed from November 14, 1943 through January 15, 1944. With the memory of repressive military rule still fresh, draft age young men in Tule Lake began receiving Army draft notices. On May 3, 1944, twenty-seven young men refused to leave Tule Lake to report for their physicals. In the government's case against them, U.S. v. Masaaki Kuwabara, et al., Tule Lake’s resisters were charged with draft evasion. Their trial began July 17, 1944, in Eureka, CA, and resulted in the only affirmation of WWII's Nisei draft resisters. U.S. District judge, Louis Goodman dismissed the case, writing, "It is shocking to the conscience that an American citizen be confined on the ground of disloyalty, and then while so under duress and restraint, be compelled to serve in the armed forces, or be prosecuted for not yielding to such compulsion." The draft resisters were then freed to return to imprisonment in Tule Lake's concentration camp.

Renunciation: President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Public Law 405, allowing Japanese American citizens to renounce their U.S. citizenship and expatriate to Japan. White supremacists had long pushed to strip Nisei of U.S. citizenship and have them deported. The WRA was eager to get rid of more “troublemakers” from overcrowded Tule Lake.

Initially, fewer than two dozen Tule Lake inmates applied to renounce their U.S. citizenship. However, on December 17, 1944, it was announced that incarceration would end and the camps would close within a year. The announcement caused collective shock in Tule Lake. Inmates were swept up in panic, consumed by anger, confusion and anxiety over thoughts they would be sent into hostile white communities with the war against Japan still going on. Tule Lake was in chaos, with inmates trying to figure out the best course of action to protect themselves and their families.

When army personnel began asking inmates if they planned to renounce and remain in Tule Lake, the message was clear; renunciation would allow a family to remain safe in Tule Lake until the war was over. In the next several weeks, thousands of Japanese Americans in Tule Lake gave up their seemingly worthless citizenship. Some rejected their U.S. citizenship to express anger at America's injustice; others did so out of worry their families would be separated if the Issei were deported. Many renounced so they could remain at Tule Lake until the war ended, blaming coercion by pro-Japan bullies, who, like agents provocateurs, goaded others to renounce but did not do so themselves. Within a few months, however, it became clear to the majority of those in Tule Lake who renounced that rejection of their American citizenship was a tragic mistake. Attempts to reverse their renunciations received little cooperation from the Justice Department.

Wayne Collins, the San Francisco civil liberties attorney who was instrumental in closing down Tule Lake's infamous military stockade, managed to derail the Department of Justice plans for mass deportations. On November 13, 1945, only two days before a ship filled with both willing and unwilling Japanese Americans departed for Japan, Collins obtained a court order that forbade their deportation until the matter could be heard before a judge. Collins charged that the renunciation program was a fraud, the result of duress caused by the mass incarceration and the pressure-cooker environment of Tule Lake.

7 members of the Fair Play Committee including Frank Emi, and journalist James Omura are arrested for “unlawful conspiracy” to aid draft resisters. They were convicted and sent to the federal penitentiary at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas except for James Omura; the convictions of the others were overturned in 1945.

1945

“All Center Conference” Letter, Statement of Facts and Recommendations looking ahead to the resettlement issues the prisoners would face upon release from the camps. These documents were sent to Dillon S. Meyer, National Director of the WRA, with a copy to Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior. These documents were signed by delegates from multiple camps. The Statement of Facts spoke bluntly about the “complete destruction of financial foundations built during over half a century” caused by the incarceration, the acute shortage of housing and fears of physical violence they would face upon release from the camps. The Recommendations included a call for federal aid grants, the low-rate long-term loans to assist the re-establishment of businesses, for the government to un-freeze Issei assets that it had frozen, and for government compensation for losses to property that had occurred during and as a result of the incarceration. Hence, the call for redress/reparations was already being made by Japanese Americans during the incarceration.

250 prisoners protested the punitive removal of three men to another camp. After a scuffle broke out, Border Patrol agents who were guarding the facility used tear gas grenades, batons, resulting the serious injury of four internees.

1946

In early 1946, two Japanese Americans — Jyuichi Sato and Andrew Shiga — were among 83 other conscientious objector strikers who participated in one of the longest work strikes in Civilian Public Service (CPS) camp history to protest racial segregation. Many Conscientious Objectors, including some Japanese Americans, were also used by the U.S. military as guinea pigs for dangerous medical experiments such as starvation, poison gas, being injected with malaria, prolonged periods of immobility, etc.

In February 1946, the national board of the JACL met during the Ninth Biennial National Convention in Denver, Colorado, and discussed what position they would take regarding all those who had protested their wartime treatment, including those who had renounced their citizenship and requested repatriation to Japan, "No-No" resisters, and draft resisters. The board formally condemned all of them as disloyal.

On 5/11/2002, the JACL held a public ceremony in which it recognized the Nisei draft resisters as "resisters of conscience" and apologized for its wartime condemnation of the draft resisters.

At their August 2019 national convention, the JACL adopted a significant resolution of recognition and apology to the Tule Lake incarcerees who had been unjustly labeled “disloyal” by the War Relocation Authority and JACL, and who were ostracized and isolated within the Japanese American community long after release from the camps. This step has helped open the door to healing long-standing rifts in the community.

Tule Lake Segregation Center is the last of the 10 main concentration camps to shut down. Tule Lake was the main place where protestors and people who had been accused of being “disloyal” for answering anything other than “yes-yes” to Questions #27 and 28 on the Loyalty Questionnaire or for being a “troublemaker” were sent to. Tule Lake was the most punitive, militarized and brutally repressive of all the concentration camps. Anyone and everyone who had been in Tule Lake regardless of any actual evidence of “disloyalty” was unjustly stigmatized by many people from the other camps as being “the bad ones”, or it was assumed they were “no-no” boys or “no-no” families, which was sometimes not even the case. For many, being ostracized and living with painful social isolation has continued for many decades after release from camp.

Japanese Latin Americans took legal action in an attempt to avoid deportation to Japan. 2,264 Japanese Latin Americans had been forcibly kidnapped from Peru and 12 other Latin American countries by the U.S. government to be used for prisoner of war exchanges with Japan. With little recourse under the United States Constitution, Japanese Latin Americans lodged their complaints with the Spanish Embassy, the designated "protecting power" for the Japanese in the United States. Many of the requests, especially later in the war, concerned the reunification of families. Most were still being held in the DOJ camps at Santa Fe and Crystal City and then classified as illegal immigrants once the war ended. The Peruvian government only allowed 80 of the Japanese Peruvians to return home. Some Japanese Latin Americans ended up having to go to Japan, while some managed to stay in the U.S.

In 1946, Wayne M. Collins and A.L. Wirin, attorneys with the American Civil Liberties Union, helped 364 Japanese Peruvians obtain "parole" at Seabrook Farms, a truck farming plant in New Jersey. They worked as undocumented immigrants until a change in immigration law in 1952.

The U.S. government later offered to pay only a quarter of the reparations amount to the Japanese Latin Americans that Japanese Americans had received, on the grounds that they had been illegal aliens -- even though it was the U.S. government who had kidnapped them and brought them to the U.S. against their will. The fight to correct this serious injustice continues.

July 14, 1946 Heart Mountain draft resisters are released from McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary. All Japanese American draft resisters were later pardoned by President Truman in 1947.